Chapter 10. Ideas and Inspiration

There are an infinite number of concurrency related topics, algorithms, data structures, anecdotes, and other potential chapters that could be part of this book. However, we’ve arrived at the final chapter and it’s almost time for us to part ways, hopefully leaving you with an excited feeling of new possibilities and ready to apply new knowledge and skills in practice.

This final chapter’s purpose is to provide inspiration for your own creations and future work by showing you some ideas that you can study, explore, and build on your own.

Semaphore

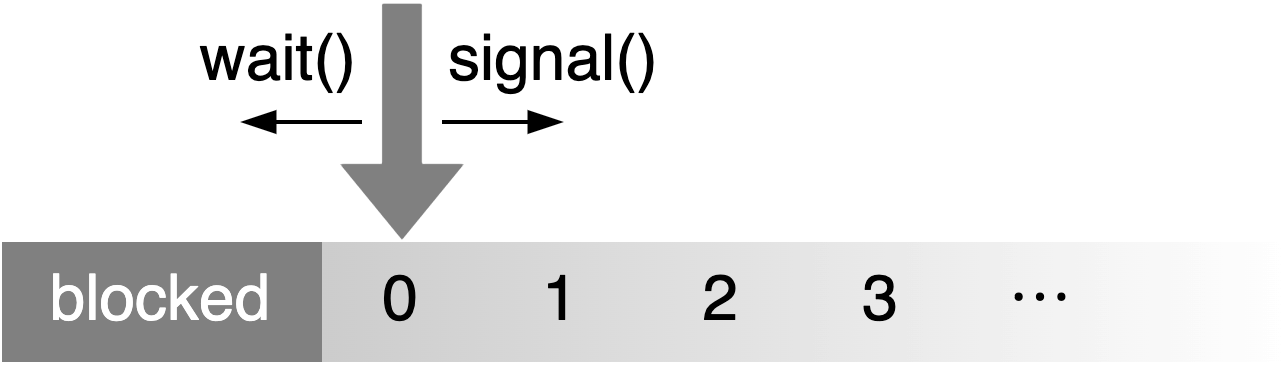

A semaphore is effectively just a counter with two operations: signal (also called up or V) and wait (also called down or P). The signal operation increments the counter up to a certain maximum, while a wait operation decrements the counter. If the counter is zero, a wait operation will block and wait for a matching signal operation, preventing the counter from ever becoming negative. It is a flexible tool that can be used to implement other synchronization primitives.

A semaphore can be implemented as a combination of a Mutex<u32> for the counter and a Condvar for wait operations to wait for.

However, there are several ways to implement it more efficiently.

Most notably, on platforms that support futex-like operations ("Futex" in Chapter 8),

it can be implemented more efficiently as a single AtomicU32 (or even AtomicU8).

A semaphore with a maximum value of one is sometimes called a binary semaphore,

and can be used as a building block with which to build other primitives.

For example, it can be used as a mutex by initializing the counter at one,

using the wait operation for locking, and the signal operation for unlocking.

By initializing it at zero, it can also be used for signaling, like a condition variable.

For example, the standard park() and unpark() functions in std::

can be implemented as wait and signal operations on a binary semaphore associated with the thread.

Note how a mutex can be implemented using a semaphore, while a semaphore can be implemented using a mutex (and a condition variable). It’s advisable to avoid using a mutex-based semaphore to implement a semaphore-based mutex, and the other way around.

Further reading:

RCU

If you want to allow multiple threads to (mostly) read and (sometimes) mutate some data, you can use an RwLock.

When this data is just a single integer,

you can use an atomic variable (such as AtomicU32) to avoid locking, which is more efficient.

However, for larger chunks of data, like a struct with many fields,

there’s no available atomic type that allows for lock-free atomic operations on the entire object.

Just like every other problem in computer science, this problem can be solved by adding a layer of indirection. Instead of the struct itself, you can use an atomic variable to store a pointer to it. This still doesn’t allow you to modify the struct as a whole atomically, but it does allow you to replace the entire struct atomically, which is nearly as good.

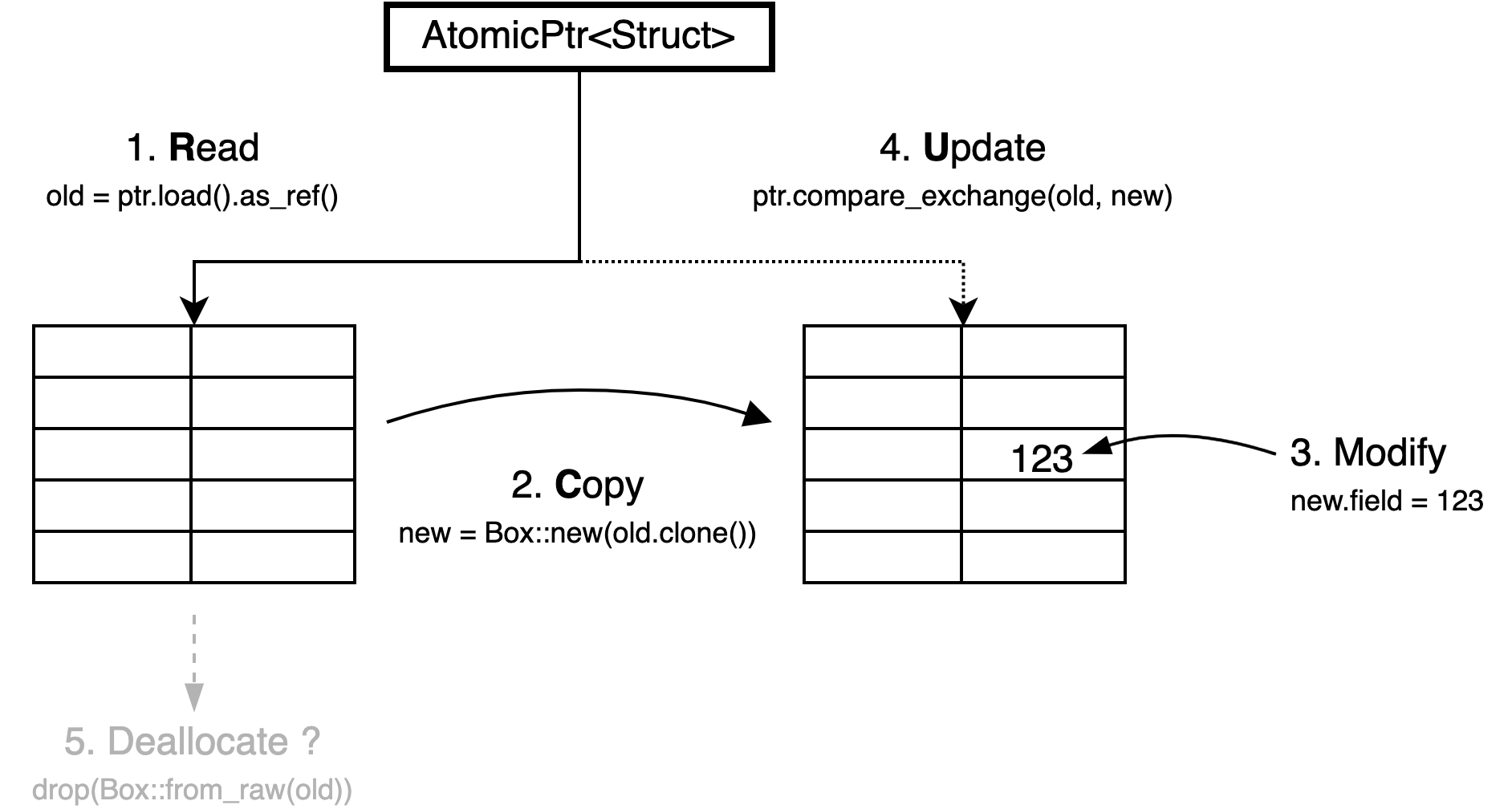

This pattern is often called RCU, which stands for "read, copy, update," the steps necessary to replace the data. After reading the pointer, the struct can be copied into a new allocation that can be modified without worrying about other threads. When ready, the atomic pointer can be updated using a compare-and-exchange operation ("Compare-and-Exchange Operations" in Chapter 2), which will only succeed if no other thread has replaced the data in the meantime.

The most interesting part about the RCU pattern is the last step, which does not have a letter in the acronym: deallocating the old data. After a successful update, other threads might still be reading the old copy, if they read the pointer before the update. You’ll have to wait for all those threads to be done before the old copy can be deallocated.

There are many possible solutions for this issue,

including reference counting (like Arc), leaking memory (ignoring the problem),

garbage collection,

hazard pointers (a way for threads to tell the others what pointers they are currently using), and

quiescent state tracking (waiting for each thread to reach a point at which it is definitely not using any pointers).

The last one can be extremely efficient in certain conditions.

Many data structures in the Linux kernel are RCU based, and there are many interesting talks and articles about their implementation details that can provide a great deal of inspiration.

Further reading:

Lock-Free Linked List

Expanding on the basic RCU pattern, you can add an atomic pointer to the struct to point to the next one, to turn it into a linked list. This allows for threads to atomically add or remove elements on this list, without having to copy the entire list for every update.

To insert a new element at the start of the list, you only have to allocate that element and point its pointer at the first element in the list, and then atomically update the initial pointer to point to your newly allocated element.

Similarly, removing an element can be done by atomically updating the pointer before it to point to the element after it. However, when multiple writers are involved, care must be taken to handle concurrent insertion or removal operations on neighboring elements. Otherwise, you might accidentally also remove a concurrently newly inserted element, or undo the removal of a concurrently removed element.

To keep things simple, you can use a regular mutex to avoid concurrent mutations. That way, reading is still a lock-free operation, but you don’t have to worry about handling concurrent mutation.

After detaching an element from the linked list, you’ll run into the same issue as before: waiting until you can deallocate it (or otherwise claim ownership). The same solutions we discussed for the basic RCU pattern can work in this case as well.

In general, you can build a wide variety of elaborate lock-free data structures based on compare-and-exchange operations on atomic pointers, but you’ll always need a good strategy for deallocating or otherwise reclaiming ownership of the allocations.

Further reading:

Queue-Based Locks

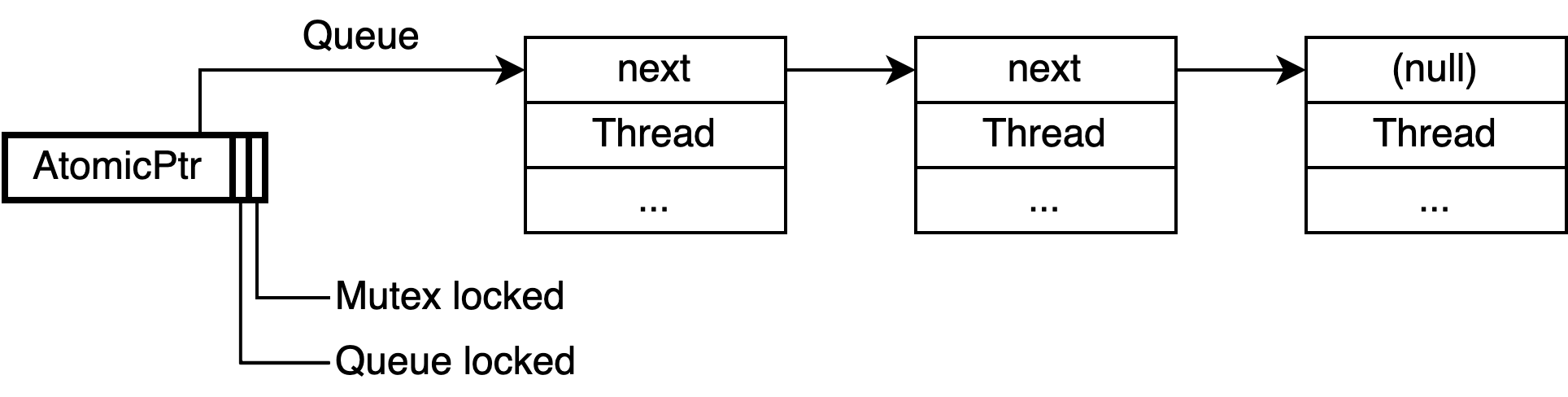

For most standard locking primitives, the operating system’s kernel keeps track of the threads that are blocked on it, and is responsible for picking one to wake up when asked to do so. An interesting alternative is to implement a mutex (or other locking primitive), by manually keeping track of the queue of waiting threads.

Such a mutex could be implemented as a single AtomicPtr

that can point to a (list of) waiting threads.

Each element in this list needs to contain something that can be used to wake up

the corresponding thread, such as a std:: object.

Some unused bits of the atomic pointer can be used to store the state of the mutex itself,

and whatever is necessary for managing the state of the queue.

There are many variations possible. The queue could be protected by its own lock bit or it could be implemented as a (partially) lock-free structure. The elements don’t have to be allocated on the heap, but could be local variables of the threads that are waiting. The queue could be a doubly-linked list with not only pointers to the next element, but also to the previous element. The first element could also include a pointer to the last element to allow efficiently appending an element at the end.

This pattern allows for implementing efficient locking primitives using only something that can be used to block and wake up a single thread, such as thread parking.

Windows SRW locks ("Slim reader-writer locks" in Chapter 8) are implemented using this pattern.

Further reading:

Parking Lot–Based Locks

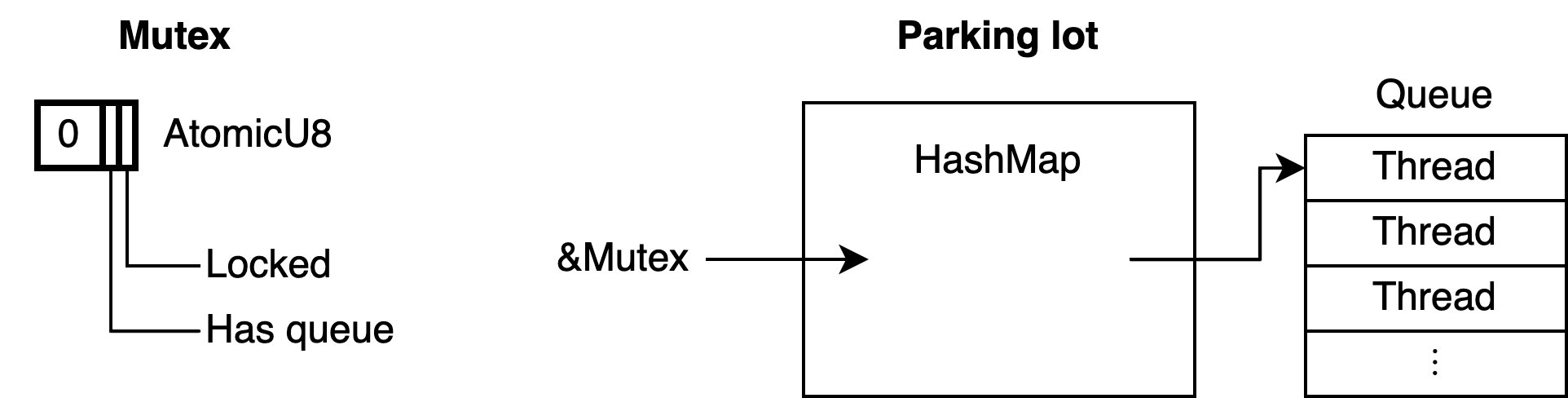

To make a highly efficient mutex that’s as small as possible, you can build upon the queue-based locks idea by moving the queue into a global data structure, leaving only one or two bits inside the mutex itself. This way, the mutex only needs to be a single byte. You could even put it in some unused bits of a pointer, allowing for very fine-grained locking at almost no extra cost.

The global data structure can be a HashMap that maps memory addresses to a queue of threads waiting on the

mutex at that address.

This global data structure is often called a parking lot, since it’s a collection of parked threads.

The pattern can be generalized by not only tracking queues for mutexes, but also for condition variables and other primitives. By tracking a queue for any atomic variable, this effectively provides a way to implement futex-like functionality on platforms that don’t natively support that.

This pattern is most well known from its 2015 implementation in WebKit,

where it was used for locking JavaScript objects.

Its implementation inspired other implementations, such as the popular parking_ Rust crate.

Further reading:

Sequence Lock

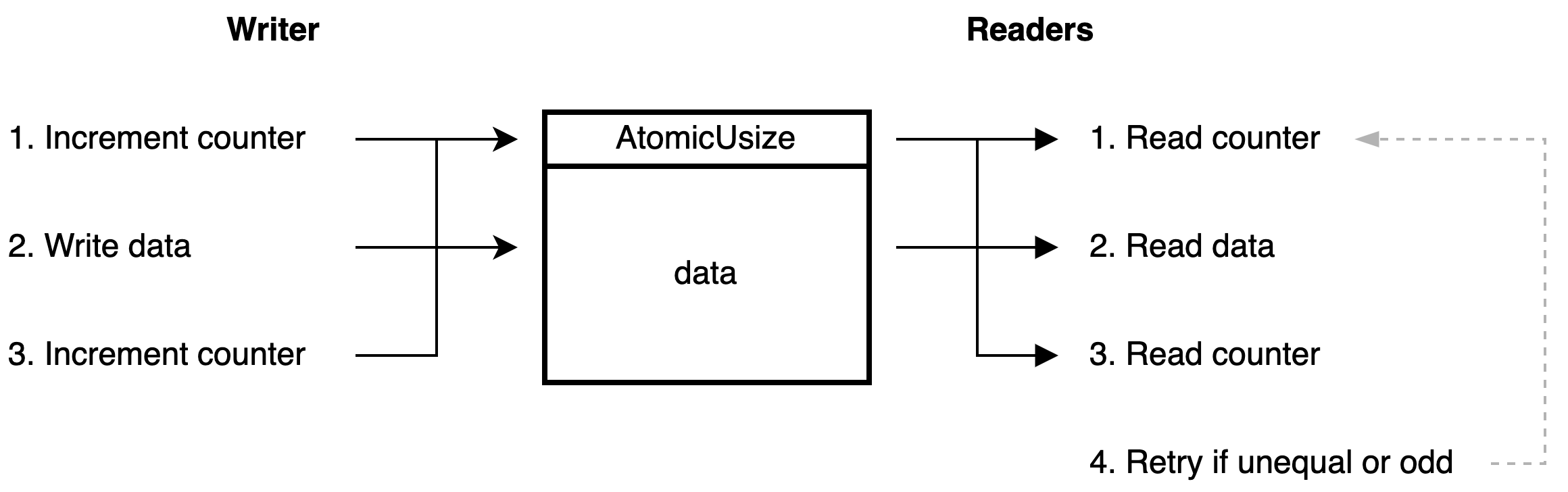

A sequence lock is another solution to the problem of atomically updating (larger) data without using traditional (blocking) locks. It uses an atomic counter that is odd while the data is being updated, and even when the data is ready to be read.

The writing thread will have to increment the counter from even to odd before mutating the data, after which it has to increment the counter again to leave it at a (different) even value.

Any reading thread can, at any point and without blocking, read the data by reading the counter both before and after. If the two values from the counter are equal and even, there was no concurrent mutation, meaning you read a valid copy of the data. Otherwise, you might have read data that was concurrently being modified, in which case you should just try again.

This is a great pattern for making data available to other threads, without the possibility of the reading threads blocking the writing thread. It is often used in operating systems kernels and many embedded systems. Since the readers need only read access to the memory and no pointers are involved, this can be a great data structure to safely use in shared memory, between processes, without needing to trust the readers. For example, the Linux kernel uses this pattern to very efficiently provide timestamps to processes by providing them with read-only access to (shared) memory.

An interesting question is how this fits into the memory model. Concurrent non-atomic reads and writes to the same data result in undefined behavior, even if the read data is ignored. This means that, technically speaking, both reading and writing the data should be done using only atomic operations, even though the entire read or write does not have to be a single atomic operation.

Further reading:

Teaching Materials

It can be great fun to spend many hours—or years—inventing new concurrent data structures and designing ergonomic Rust implementations of them. If you’re looking for something else to do with your knowledge on Rust, atomics, locks, concurrent data structures, and concurrency in general, it can also be very fulfilling to create new teaching materials to share your knowledge with others.

There is a great lack of accessible resources aimed at those new to these topics. Rust has played a significant role in making systems programming more accessible to everyone, but many programmers still shy away from low-level concurrency. Atomics are often thought of as a somewhat mystical topic that’s best left to a very small group of experts, which is a shame.

I hope this very book makes a significant difference, but there is so much space for more books, blog posts, articles, video courses, conference talks, and other materials about Rust concurrency.

~

I'm excited to see what you create.

Good luck. ♥